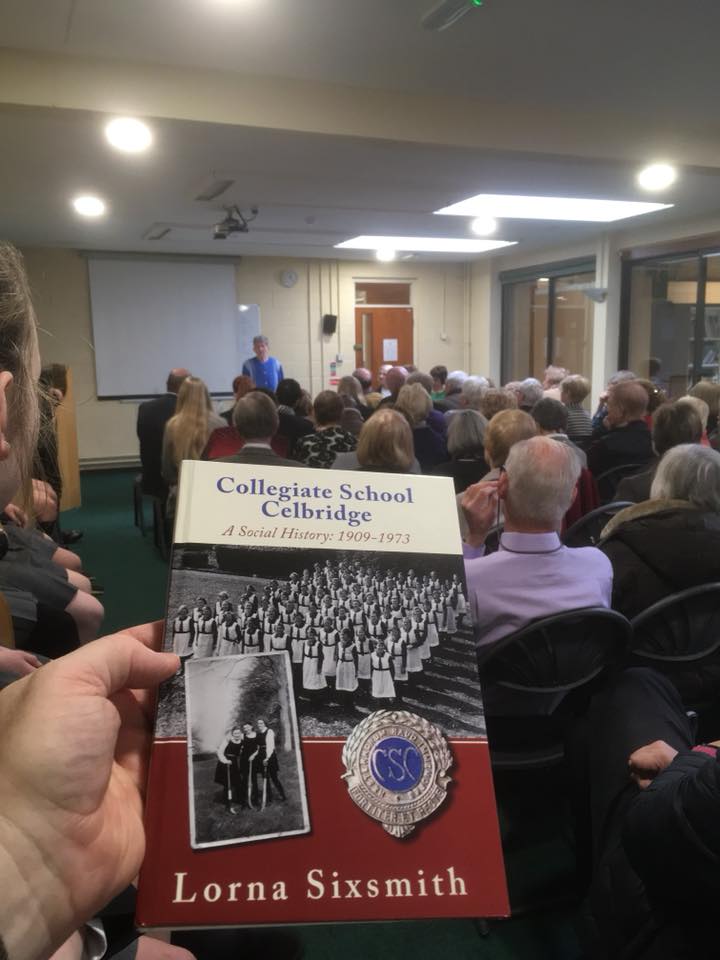

This time last year, my editor and formatter Sally Vince was putting the finishing touches to the book I had just finished, a social history of the Collegiate School Celbridge. The all-girls school had merged with the boys’ school Kilkenny College in 1973 (where I went to secondary school in the 1980s as it happened) and past pupil, teacher and headmistress Miss Freda Yates, now in her 90s, had been looking for someone to write a book about the school. She wanted a social history, stories of what the pupils experienced in their everyday school lives. I’ve always had an interest in social history and each of my three humourous books on farming contain historical research into farming past and present. When asked to do it, I thought it would be interesting and a lot less work than it turned out to be. I was expecting to write a pamphlet of about 15,000 words not a hardback book of over 50,000 words complete with photos from over the decades. But it was a book I enjoyed writing and I’m really pleased with the finished product. The book focuses on the years 1909 – 1973 with a brief history of the school in earlier centuries.

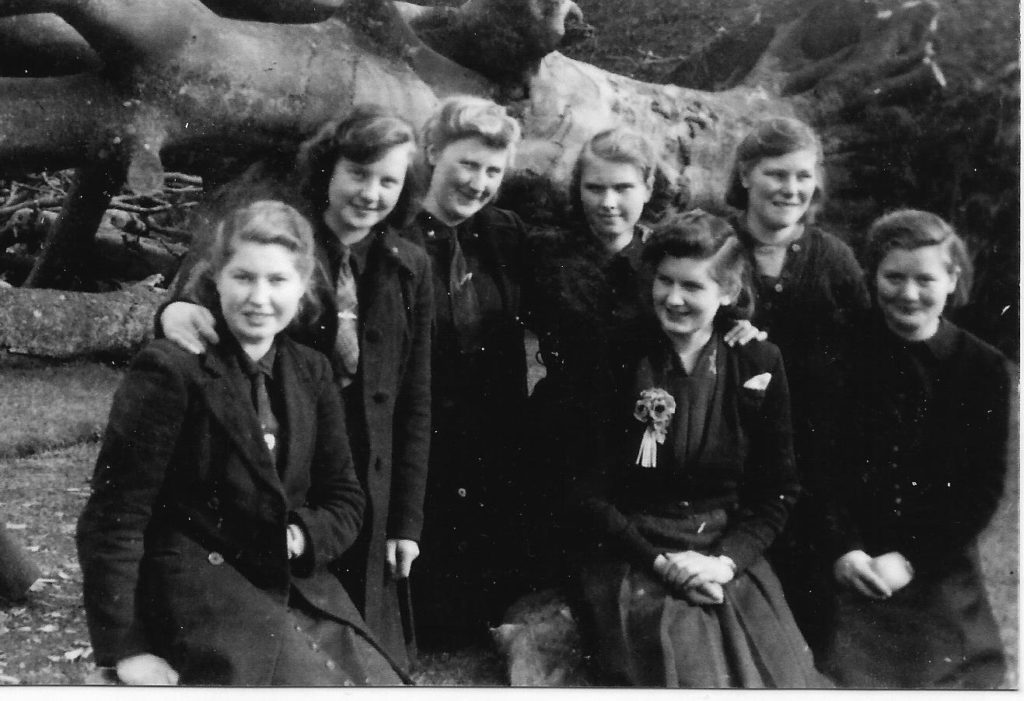

There was a tremendous amount of material in the school archives, including many issues of the school magazine The Celbridgite. I met up with past pupils too. Many ladies in their 80s and 90s were there in the 1940s and were still good friends, meeting up regularly at the Past Pupil annual dinner and other events.

There was a tremendous amount of material in the school archives, including many issues of the school magazine The Celbridgite. I met up with past pupils too. Many ladies in their 80s and 90s were there in the 1940s and were still good friends, meeting up regularly at the Past Pupil annual dinner and other events.

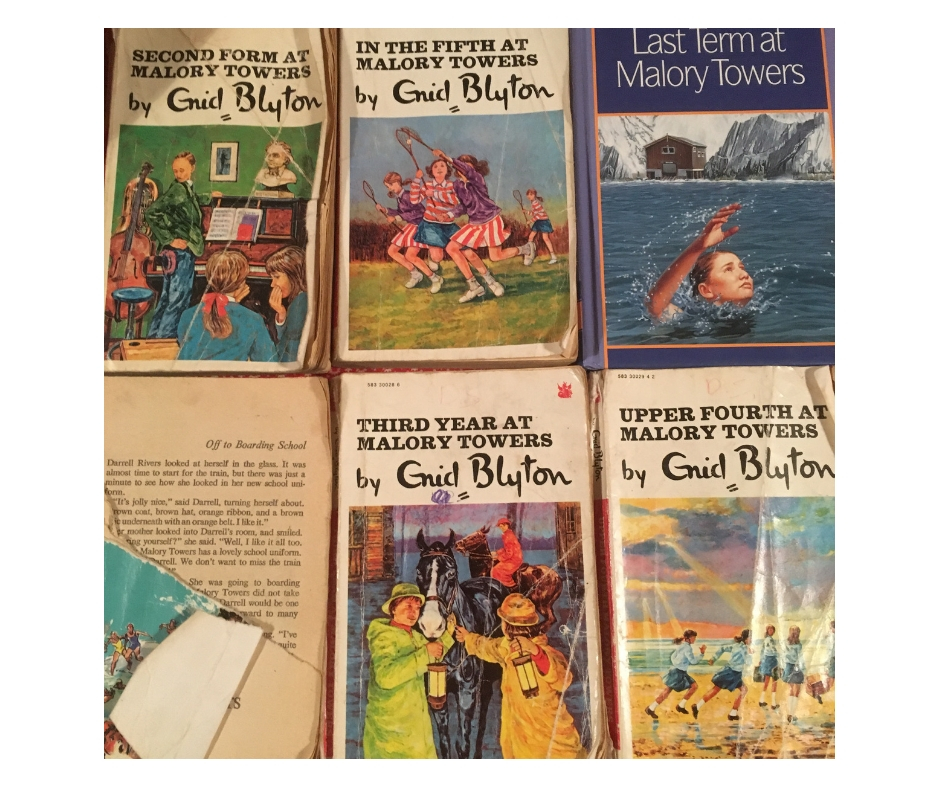

My editor, in her wisdom, told me that some readers would not be interested in a comparison between Celbridge and Malory Towers (especially as the latter was fictional), that they were buying the book to read about Celbridge, and that some may never even have heard of Malory Towers. I was horrified! Never heard of Malory Towers! I couldn’t imagine such a travesty. But I did see her reasoning and hence, I killed my darlings, removing all mention of Malory Towers. And yes, the book is the better for it. However, I kept the draft and am publishing it here because I do believe there are some people out there who would be interested in the comparison, so if you are one of them, do read on. (A huge silver lining was that I immensely enjoyed rereading all my Malory Towers books – such a lovely trip down memory lane).

It’s a long post so if you would just like to get the hardback copy of the Collegiate School Celbridge: A Social History 1909-1973, it’s available from Kilkenny College for €15 plus postage. If you require it to be posted, send a cheque for €25 made out to Kilkenny College, to the Bursar.

How did the Collegiate School Celbridge compare with fictional boarding schools?

Enid Blyton wrote a number of books focusing on boarding school life, the most popular probably being St Clare’s (1941 to 1945) and Malory Towers (1946 to 1951). As many people seem to mention Malory Towers when saying they thought boarding school would be similar (before they went there) and it was my favourite boarding school series, I’m going to compare it to the Collegiate School Celbridge.

Four Houses

The fictional Malory Towers is set in Cornwall, a “big, square-looking building of soft grey stone standing high up on a hill” with four rounded towers making it look like “an old-time castle.”[1] The structure of the school helped with some of the plotlines. Girls were placed in one of four houses, North, South, East and West, which related to the position of the four towers, and indicated where they slept, had lessons and who were likely to be their best friends. Most of their lacrosse matches were between the houses and bad behaviour by an individual meant everyone within that house could be affected, as too many order marks meant the loss of some privileges such as a half day off school. Of course, many other fictional boarding schools often had four houses, the most famous probably being the Harry Potter series with Gryffindor, Ravenclaw, Slyterin and Hufflepuff.

My much loved copies of Malory Towers

Celbridge also had four houses. They were typically known as colours White, Red, Blue and Green. In acutal fact, three were named after people who invested a lot of time and energy in the school: Kingsmill Moore (red), Seymour Harrison (blue) and Charles O’Connor (green). The White house represented Hope. Inter-house competitions included various sports such as basketball, hockey, tennis and cricket. They also competed in debating teams and spelling contests.

Background of Pupils

Malory Towers girls came from much more affluent backgrounds, for example, Zerelda’s grandmother had a butler, Darrell’s family had numerous staff including a gardener, Mary Lou’s mother got a French au pair to look after her during the summer holidays, and one girl had the title “Honourable”. Only one Malory Towers pupil was there under a scholarship and at one point, she was accused of theft, perhaps suggesting that poor people weren’t so trustworthy. Celbridge was jokingly known as the “school for poor Protestants” as most pupils were awarded scholarships. Apparently, of secondary school girls from Co. Cork, fee-paying girls went to Rochelle while scholarship girls went to Celbridge.[2]

Arriving at School

The method of travel to both schools was similar in the 1940s. Although a few arrived by car, most travelled by train or bus. As it was often late in the evening by the time girls arrived at their fictional or real school, their trunks were left until the next day to unpack. All girls brought a small night bag containing what they needed for the first evening: nightwear, toothbrush, soap and money. It was a long day of travelling so once they had eaten; it was time for an early night. One pupil, arriving at Celbridge for the first time in 1934, recalled arriving cold and miserable from being travel sick on a long bus journey. Many parents travelled with their daughters the first time and were sad leaving them behind. Jessie Bourke’s father brought her on the train from Westport for her first day in the school. He had to stay overnight with a relative in Dublin before returning the next day. When he got home, he wanted to go straight back for her.

Prefects 1945-1946

As girls got older (and braver), those who got the bus to Celbridge used to get the driver to drop their trunks at the gate, knowing the handyman Daly would bring them in, using a contraption similar to a wheelbarrow. The girls then continued on the bus journey to Dublin where they went to the pictures before returning to school for the next term.

When they unpacked their trunks the next day, uniforms were checked by a teacher. Celbridge girls recall having to lay everything out on their bed, each item was checked to ensure it was labelled with name tapes.

Dormitories

The Malory Towers first year dormitory sounds cosy and colourful with its ten white beds each with a different coloured eiderdown, each divided by a white curtain which could be drawn or pulled back. Each cubicle had a cupboard, chest of drawers and a mirror. The washbasins at the end of the room had hot and cold water.[3]

The Celbridge dormitories were more spartan. The first-year and second-years slept in two long rooms. There were about twenty beds in each, lined up in two rows with a narrow pathway in between. The large sash windows were curtain-less. Each bed was separated from the next by a chair on which the clothes for the next morning were left. The chairs were also used to sit upon when washing their feet at night and each morning when they had to fine comb their hair by brushing it one hundred times. The girls were allowed to bring back a woollen foxford rug but they had to be placed under the thin bedspreads.

Before a washroom was built in 1948, the girls used washbowls. The three legged wrought iron stands had a basin on the top circle with a brass stopper in it; a white enamel bucket was placed on the bottom rung under the basin. Their towels and wash bags hung on the rails beside the basins. Every evening, the girls collected warm water from the washroom in their jugs for their night ablutions; they then emptied their buckets and collection fresh water for morning washing. The water may have been warm when it arrived but by the next morning it often had ice covering it. At the end of the dorm was a row of narrow cupboards, numbered, one for each student. They had two shelves and a hanging area.

Students from years 3, 4 and 5 slept in dorms called Cubicles – they were Dorm 7, the Cylinder Room, The Music room and Dorms 10, 11 and 12 were in the attics. Older students slept in the four-bedded rooms on the first and second floors and in the garret which was the favourite sleeping quarters as long as you weren’t in the room above Miss O’Connor’s (the headmistress) suite.

It was extremely cold in Celbridge, and most girls suffered with chilblains which made walking and writing painful. HGreen enamel stoves heated the classrooms. They were fuelled morning and evening by Ronnie Darlington, the handyman, with anthracite. The schoolroom was heated by large radiators fuelled from the boiler house which also heated water for the washrooms and bathrooms. The girls huddled around the stoves and heaters any chance they got in the cold months with each class congregating around different heaters. The heating in the dormitories was described as “very inefficient”. The windows were bare and the bedclothes were thin. Girls wore bedsocks and bed jackets in bed and they brought a rug from home for extra warmth. One pupil said that her legs were almost permanently numb from her knees to her toes during the winter months. Although there are mentions of races to a radiator and the occasional lighting of a fire in Malory Towers, it always seemed cosy and warm to readers. The only girls that got chilblains and colds were the ones too lazy to do sport so it was viewed as their own fault.

The Routine of the Day

Each morning in Celbridge, after washing, dressing and brushing their hair in silence, it was time to sort out their beds. First they had to air their beds by folding their blankets at the end of the bed and turning the mattress back over so half of it lay across the blankets. The beds were then made after breakfast and had to be re-made if not left neat. Prefects slept in dorms of the younger years, one to each dorm, and they supervised the making of the beds.

The girls then walked along the long corridors to reach the School Room, many remember the corridors having an intimidating and forbidding atmosphere. The girls gathered for prayers in this long rectangular room with its platform at one end, just as girls in Malory Towers attended prayers each morning. They lined up in rows with about ten pupils per row. Arranged by height, the smallest girls stood at the front. When arranged into positions at the start of the year, girls often stood on tiptoes or hunched down in attempts to stand by their friends for the year. Anyone small in height was destined to be in the front row for all her years in school. Tall first years weren’t overly comfortable having to stand with fourth or fifth years. One girl played the piano for the hymns and continued playing as the girls marched out in single file to go to the Dining Hall. “We marched everywhere” chorused a number of ladies who attended in the 1940s, “We marched from class to class, from assembly to breakfast, after class to put our books away in our lockers, we marched to bring our desks to the schoolroom, we marched from evening study to tea and back again.” Perhaps it was seen as a means to warm them up as well as maintaining order.

In Celbridge, the religious theme continued with the singing of Grace before and after each meal. “For what we are about to receive, May the Lord make us truly thankful – Amen” and “May the Grace of Christ our Saviour, With the Holy Spirits favour. Rest upon us from above, thus may we abide in union, with each other and the Lord. And possess in sweet communion, Joys which Earth cannot afford.”

In Malory Towers, girls sat in their year groups for meals, whereas there were seven at each oval table in Celbridge. A senior pupil sat at the head of the table and the other six were an assortment from the younger years. This gave girls the chance to get to know others and ensured that the older pupils could ensure a high standard of behaviour and manners. The staff sat at a large rectangular table on one end. Girls brought their own set of cutlery to school. Parents had to engrave their names on the handles with a hot needle. As the cutlery inevitably got mixed up, sometimes a less expensive knife or fork was scorned by some girls.

After breakfast, the girls walked to Kiladoon Gates in a crocodile of twos. If there was even a cloud in the sky, they had to bring their paraphernalia (mack and umbrella) and wear wellingtons. They passed a farmyard at the bend in the road, and they nicknamed it “Eau de Cologne Corner” because of the stench of slurry. If they were caught trying to turn back too early, they had to go the whole way again.

Drill was from 8:50-9:15 on alternate mornings. This involved various arm exercises and a goosestep. The girls then got their fold up desks and put them into place in the relevant classrooms. They got their books from their lockers and put them by the desk. If their pencil boxes were made of tin, they had to be left on the floor in case it fell and caused a disturbance in class or prep.

Class started at 9:20 with classes being of 40 minutes duration, with classes ending at 3:30. Subjects included Irish, French, Mathematics, Commerce, Geography, English, Scripture, Botany, History, Needlework, and Domestic Science with extra Irish on a Saturday morning from 11:30-1 for some classes. Subjects in Malory Towers included English, Maths, History, Geography and French. There was very little mention of subjects like Domestic Science with only an occasional reference to a sewing room and girls darning their own clothes. Malory Towers didn’t seem to emphasize the need to learn all the domestic skills that were expected of women at this time. There didn’t seem to be an expectation of girls to need to learn to cook, sew or garden. Was that because they were upper middle class and it was expected they would have staff to do those jobs?

Pupils in the fictional school had to do some chores but they didn’t seem to be too onerous, with mentions of tasks like arranging flowers in their common rooms. In contrast, the Celbridge girls rang bells, mended their clothes, dusted surfaces, swept floors, made desserts, fetched milk, set tables, cleared tables, cleaned floors and made sandwiches and apple tarts. Their desks had to be sanded and polished every Saturday morning before being inspected by a teacher to check all the ink spots and other marks were gone. A pupil was rubbing at a stubborn ink spot one Saturday morning. A teacher came along to inspect her progress and told her to use “more elbow grease”. Perplexed and having never heard the term before, the pupil replied “We don’t have elbow grease at home”.

At the end of class, each desk had to be folded and placed against the wall and books put away. A member of staff checked the book lockers to check they were tidy. Some members of staff, if they spotted something projecting out from under a book, would pull it all out and show that the back of the locker was like a “Magpie’s nest”.

The afternoon was spent doing sport or some gardening. After their afternoon recreation, the girls had to retrieve their desks and bring them to the School Room for evening study. The first year girls sat in the front, in rows of eight across the room, followed by second years and so on. They then filed out in rows to get books from their lockers. A couple of girls brought in inkwells on trays; each girl took one and placed it in the hold on the ledge of the desk. These were collected again at the end of study before the desks were folded and put away again. They stopped for tea in the middle of evening study and had a break of half an hour.

Just as many Malory Towers girls worked hard to succeed in examinations (although we never heard what grades were awarded); the academic standard of Celbridge was high with a good work ethic.

Sport

Playing hockey in 1946

The main sports played in Malory Towers were lacrosse, tennis and swimming. If girls had their own horses, which could be housed in the stables, they could go horse-riding. Celbridge pupils played hockey and had matches against other schools. The hospitality was enjoyed as much as the sport as they provided the visiting teams with tea. The girls made the sandwiches and apple tarts. They particularly liked going to the “Hall” school as they provided crumpets by the fire for their visiting teams. In the summer, they played basketball on the hockey field; they also played cricket and tennis. For girls who loved games, there were many competitions between the four houses too. Girls who won the most points for their house had their name inscribed on the relevant cup. One girl remembers drawing with another girl for the overall Sports cup; the winner was decided by a relay race of four runners from each house. Her house lost but she won the following year and had her name inscribed on the cup then.[4] Girls who weren’t so keen on sport sometimes avoided it by hiding in one of the outside toilets and reading a book when the others departed.

Uniform

How did the uniforms compare? On the opening page of the first Malory Towers book, Darrell Rivers is admiring her new school uniform in the mirror: a brown coat, brown hat, orange ribbon and a brown tunic with an orange belt.

The Celbridge girls wore fully lined and button through navy serge dresses with black stockings and a navy coat and beret. The suspenders were a challenge for many on the first morning and yes, some had drooping stockings as they headed to breakfast. One girl brought a corset but gave up on it when she found it impossible to manoeuvre under her dressing gown in a dormitory of over twenty girls. They wore navy gym tunics with a white blouse for games and if it was very hot in the summer months, they were allowed to wear the gym tunics then too. They had a special pinafore, coat and hat for Sundays with a blazer or coat. Each girl had an impressive array of footwear: indoor shoes, outdoor walking shoes, slippers, galoshes, wellingtons and hockey boots.

1930s – the occasion was the laying the foundation stone for the building of a new library

On “special days”, the girls had to wear white spotted muslin pinafores over their navy serge dresses. The school tie came out over the pinafore. These occasions included visits from school inspectors, examination days and visiting days.

The girls always enjoying seeing what style the teacher on duty would be wearing to church. They themselves sometimes resorted to desperate measures to pass muster and look smarter such as using black shoe polish to cover up a hole in a stocking and using a three penny bit to secure a stocking if a suspender broke.

Tricks & Misdeamours

The Malory Towers books contain detailed descriptions of tricks played on teachers with Madame Dupont being the most popular victim. These included sneezing powders, invisible chalk and bloating balloons. Did the Celbridge girls play tricks on each other or on teachers?

One common trick was to place an item over a door so once the door was pushed open, the item fell on the person’s head. If a member of staff was seen or heard, “Nix” was the warning word.

One girl remembers getting into serious trouble. She had been excused from study to go to the toilet. This meant going through the dimly lit corridors that led to the entrance to the Dining hall, which was equally shadowy. As she was about to step in at the darkened end, a girl (who happened to be of a nervous disposition) came through from the toilets. The trickster ducked under a table then bounded out on all fours. The poor girl screamed and screamed and the trickster received a severe ticking off in assembly and was sent before Miss O’Connor.

The girls had made a pet of a terrier dog from the lodge but didn’t manage to teach it “no” or “stay”. One Sunday he followed them to church, refused to remain outside on his own and in spite of many of their efforts to stop him, he dashed up to the communion rail right in front of Major Connolly and Lady Carew. His antics weren’t appreciated and the girls had to plead ignorance and innocence.

While the following aren’t tricks, the memories of things that teachers and pupils did or said, are amusing too.

Like all French teachers, Miss Fulcher expected her pupils to learn French verbs. If a pupil didn’t know them, she had to write them out and learn them for the next day. On one occasion, a very gifted girl did not know these verbs and was dealt with in the customary way. Next day she was questioned but there was no response from her. As everyone waited, almost with bated breath, one brave girl ventured “she has eaten them”. She was so unaccustomed to having work returned that in a fit of rage and frustration, she ate the paper on which she had written the verbs.

Irish was viewed as an important subject in Celbridge and reports show that its pupils did well in it. One day, when testing pupils on their language skills, a teacher asked “what would you say if you heard I had just died?” “Buíochas le Dia! was the response she got from one girl. (Thanks be to God)

The teachers were sticklers for correct grammar and speech. If Miss Lynd asked a girl the time at around 2:30pm. If the girl replied “half two” instead of “half past two”, Miss Lynd used to reply with “half two is one”. To encourage good posture in her pupils, Miss Lynd used to say, “Bosoms off the tables girls!”

Similarly, if girls asked “can I go the village?” the answer was “whether you may or not is another thing”.

One girl remembers having thrown her school hat in the pond (on the left going up the drive) on my last Sunday there, as she knew she wouldn’t need it again. The teacher on duty was appalled and made her walk in and get it out.

Hockey Team 1955

Food

The food in Malory Towers was much better than in Celbridge. Remember these were the years during and just after the Second World War. There were shortages of various foodstuffs and coupons had to be provided due to rationing. However, there isn’t a single mention of the war or rationing within these books. Breakfast was porridge and milk (the fact milk was mentioned suggests that many people ate porridge without), scrambled eggs and toast and marmalade. A lunch was stew with all kinds of vegetables. Although the pupils used to complain occasionally about the food, it was described as “wizard” to new girls or to pupils in other schools.

The Celbridge girls had Irish stew frequently which wasn’t relished. Meat was often cooked the day before and served cold. Desserts included a white blancmange made from milk and carrageen moss which set like a jelly, cornflour with prunes, stewed apple with custard, semolina with bay leaves, jam tarts or rice pudding. Jelly or trifle was the dessert on Sundays. The jam tart was considered more like a cement slab, the pastry was often quite hard. One day while trying to manoeuvre the pastry with a spoon a piece took flight and landed beside the staff table, the culprit was asked to stand up; needless to say a different reason was expected for the flying missile.

Teas were often bread and cheese and they could bring in their own jam from their tuck box. The bread was dark in colour due to the scarcity of white flour. They remembered their mothers sieving flour through their tights in order to get enough white flour to make a cake. Butter was always very scarce, a slice of a pound for a table of 6 or 7 girls. The head of the table meticulously divided it into equal portions and each one helped herself to her share.

Most girls brought back supplements in their tuck boxes or had food posted to them. They were allowed to receive eggs and it was quite normal for girls to receive a dozen eggs packaged up in a box, with remarkably few breakages. They were allowed to bring their eggs to the kitchen before tea to boil them in order to supplement their meal.

Occasionally, there was extra protein in the soup! Girls remember one of the kitchen staff shrieking “there’s a mouse in the soup”, a dead mouse falling out of a girl’s boot, and a rat coming out from under the floor in the study hall – it appears all remained calm though as Miss Fulcher tapped her foot and told it to “shoo”. One presumes it obeyed.

Malory Towers was more lenient regarding what girls could have in their tuck boxes. Cakes and boxes of chocolates were permitted. Girls received parcels of goodies from godmothers, parents and aunts, and the contents were divided between friends in their dorm or supplied a midnight feast.

There were strict rules on bringing chocolates and cakes into the Collegiate School (in an attempt to ensure that all girls were treated equally). One lady recalls receiving knitted bedsocks from her mother in the post and she had put a treat in each sock. When the teacher checking parcels saw them, she marched her down to the kitchen, opened the front of the big black range and ordered her to throw in her precious treat. It must have been so upsetting for a homesick twelve year old. Girls learnt how to circumvent these rules. Tuck boxes had false bottoms, with enough space to hide some bars of chocolate. When a teacher checked the box, she only saw eggs, cheese and jams. The girls were allowed to receive jam. As it was usually sent in a stone 2lb jar, teachers didn’t check the contents. If they had, they’d have realised this was also the perfect size to fit a home-baked swiss roll. If any girls were going to Dublin, they were besieged with requests to buy sweets. The tuck shop was open once a week and they were limited in what they could buy, both in terms of having to provide coupons and only being allowed to spend a certain amount.

Although chocolate was forbidden, it was smuggled into the school. One male visitor secreted in bars of chocolate hidden in his plus-fours! Chocolate was also posted to them within newspaper pages. Parents had the knack of folding the papers with twine between the folds and the chocolate was secured by the twine. They were allowed to receive a cake for their birthdays and for hallow’een. The cake was shared with the other six people at the tea table and with best friends. However, some girls didn’t receive any food packages from home, their parents just couldn’t afford it.

Pupils weren’t supposed to get a parcel from home unless it was their birthday. Claire Lappin received a bar of Lemons chocolate in the post. She was told to send it back home but on realising that the size of her French grammar book was almost the same as the chocolate bar, Claire had an idea. Very conveniently, her friend Dorothy Oakley collected chocolate wrappers. She gave Claire a Lemons wrapper which was fitted perfectly on her French grammar book. The chocolate was devoured. Imagine her mother’s surprise when she opened a parcel to find a French grammar book. This rule continued for decades. A pupil of the early 1960s recalls her aunt being very adept at opening a biscuit packet, removing most of the contents and filling it up with mars bars and other contraband goodies. She resealed the packet in such a way that nobody noticed it had been tampered with. At the beginning of term when lockers were being inspected, cakes were hidden under pinafores until it was safe to hide them in the lockers again.

Visiting Days

There was only two terms in the Collegiate School before 1945, from September to Christmas and from January to June. Easter holidays only started in 1945. Malory Towers had three terms, similar to what happens now. Both the fictional and real school had visiting days where parents or other family were able to visit – there was one per term in Celbridge. While girls could go out with their parents for the day in Malory Towers, often bringing friends with them and having a scrumptious lunch, it was quite different in Celbridge. Many girls didn’t receive any visitors as their homes were so far away. Visitors had to come to the front door to be admitted and had to leave gifts in the hall to be assessed. A teacher then decided if they could be given to the recipient or returned. Visitors and pupils strolled around the gardens if the weather was fine or sat in the Schoolroom if it was raining. One pupil’s aunt always brought her a lovely selection of cakes in a box from Roberts Café on Grafton Street in Dublin. How did she smuggle them in? After the visit, they both stood either side of the garden wall. Her aunt’s coat belt was tied to the box, she lifted up her younger niece who lowered the box down over the wall to where her eager sister was waiting to untie the belt and run to hide the box of cakes.

Midnight Feasts

Did Celbridge pupils manage to have midnight feasts? Yes, they did. The Seniors were allowed to go shopping in the village on certain days. Gleeson’s confectionary shop was located half way through the village and was frequented. It probably held a similar magical atmosphere to Honeydukes in Harry Potter’s Hogsmeade. Younger pupils used to trust Seniors with their pocket money and ask them to buy them particular sweets. When in Upper Fourth in Malory Towers, Darrell and her friends had a midnight feast by the pool, even going for a midnight swim. The Celbridge girls didn’t have a pool but a group of friends had a feast by a haycock in a neighbouring field one year. Although the morning walk to Kiladoon was usually detested, a group of friends decided one bright moonlit night to dress in all their paraphernalia and go for a walk at midnight “just for the fun of it”. Midnight feasts were usually held at Hallow’een and before the end of term. Daly the gardener provided them with buckets of apples for their feasts.

Punishments

Punishments in Malory Towers could be reversed. For example, one girl wasn’t expelled as other girls spoke up for her. On one occasion, pupils had to forfeit a half holiday day off school for playing a trick on a teacher and this was considered a serious punishment. Prefects and senior pupils had “punishment books” and could write out a punishment for a younger pupil. They seemed to concentrate mostly about improving academic progress such as learning sonnets off by heart and reciting them some days later. Girls punished others for bad behaviour by sending them to Coventry meaning that no one spoke to them for a number of days.

How did punishments in a real school compare? The most common punishment was being put on silence and not being allowed to talk outside of class. If caught talking after the silence bell at night, girls had to stand in cold corridors in their dressing gowns for over half an hour. One year, on return to school after the Christmas holidays, some girls discovered that their pre-Christmas midnight feast had been discovered. They had toasted bread in the kitchen and were caught as they’d lit the fire and hadn’t cleaned out the grate afterwards. When they came back after their holidays, Miss O’Connor asked the guilty persons to step forward in assembly. Her anger was such that she “walked up and down with her eyes flashing like a caged tiger”. They were forbidden to go to the village for the rest of the term and the prefect amongst them was demoted, losing her prefectship.

A past pupil remembered spilling talcum powder on another girl in the dorm and being sent to Coventry which meant being silenced and no one else was allowed to talk to her for a week. Hester Walsh remembered when standing on the stairs in the long queue for “Black Jack” (our insides shone like our outsides), she began to hum a pretty tune and was told “You go on silence for six weeks.” Six weeks![5]

Younger girls were in awe of prefects who checked that the various chores were done properly. They didn’t dole out punishments frequently but could order the cleaning of baths, the sweeping of the schoolroom and the moving of chairs from one room to another.

Outings

This was a time when petrol was rationed; very few people owned cars and even going to Dublin was considered a major expedition. Days out in Malory Towers included picnics to a nearby hill and the situation was similar in Celbridge. It was a special treat to go on a picnic to Andrews Hill, two miles from the School. On one occasion, a hardboiled egg for each pupil was included in the picnic. Some girls founds theirs weren’t completely hard so left them, partially shelled, in the sunshine to complete the cooking process. It was a treat to be allowed to wander in to a derelict “haunted house” exploring the dates and news on old faded newspapers and seeing old wallpapers.

Later these outings developed into trips to the seaside with Howth being a popular destination. They could get shelter there if it was wet. There was a piano so one girl could play while the others danced. Going blackberry picking was also considered a nice excursion, filling the large aluminium jugs to the brim and making jam the next day. Other outings included Killiney Beach, Castletown House and Celbridge Abbey.

Illness

All girls had to bring back a health certificate at the beginning of each year. In the Malory Towers books, who could forget the irrepressible and scatter brained Irene who always mislaid her health certificate and feared that she’d be put into isolation by Matron until it turned up. It was held to be of equal importance in Celbridge. Infectious diseases such as measles and mumps were serious. The health certificate contained information on vaccinations and immunisations: smallpox, poliomyelitis, diphtheria and whooping-cough, TB/BCG. It also confirmed if they pupil had had chicken pox, measles, German measles, scarlet fever, mumps, cerebro spinal fever and/or ringworm. If they had been ill or in contact with others who had mumps or measles, they weren’t allowed back to school. Parents also had to advise if their daughter was a sleep walker, if she had heart disease, asthma or a discharge from the ear. A dental certificate was also requested, confirming that teeth were in good order.

Malory Towers had a sick bay where any ill pupils were sent, they were looked after under the careful scrutiny of Matron, and friends were allowed to visit. Celbridge didn’t have a sick bay until 1960 but isolated girls to particular dorms if necessary. One lady remembers when three of them were sick with German Measles and were confined to a room at the top of the school. Food was brought to the door and they had to use a bucket as a toilet. To make matters worse, the end of term came and they weren’t well enough to go home and had to stay for a while longer. One girl, aware that she was coming down with the disease, tried to hide it knowing she’d have to stay for part of the holidays but the rash gave her away. If severely ill or infected with a contagious disease, girls were often sent home. One girl went home ill with whooping cough at the end of January and didn’t return to school until early May. Although she was better, she couldn’t return to the school as there were a number of pupils there ill with typhus.

Teachers

All teachers lived in the school at Malory Towers, sleeping on the top floors. Some teachers lived in at Celbridge. Miss Lynd and Miss Wann travelled down from Dublin daily on the bus, walking to the school from the village. They then stayed if on duty. While some pupils felt that the school was very confined with so little interaction with others, others felt the teachers living out brought a sense of the outside world to the girls, telling them about national and international events and Miss Lynd brought the Irish Times to the School Room every day. Miss Lynd was admired immensely by her pupils; she taught English but referred to material in other subjects when teaching in order to make subject matter as relevant as possible. She was strict but fair and used to tell them “You didn’t come here just to pass exams; you came here to think for yourselves”. One past pupil remembers her Maths teacher Miss Wann saying to her “I cannot fathom your mentality; Miss Lynd tells me you’re very good at English”.

Reactions to and memories of teachers are mixed. One lady recalls feeling so humiliated when told she was unintelligent because she didn’t know the meaning of the word “lethargic” and that she had “no recollection of a single teacher ever smiling at me” whereas others remember particular teachers with fondness and respect.

The Malory Towers teachers were regarded with affection and respect, and the girls gave some fond nicknames e.g. Potty for Miss Potts. The Celbridge staff had similar nicknames e.g. Connie for Miss O’Connor, Fuss for Miss Fulcher.

Friendships

Celbridge girls made firm friendships in school. On Sundays when they wrote their letters, they used to sit in their friendship groups, known as a “ring”. They looked out for each other, shared tuck and cakes, and the friendships lasted for decades. Given the distance between their homes, they didn’t get to meet up much during the holidays although girls living near each other met up occasionally for an afternoon. The Malory Towers girls seemed to write to each other during the long summer holidays but Celbridge girls didn’t tend to do so. They often found it hard to reconnect with old primary school friends and neighbours in the holidays, as they had been away for so long and living a very different life. Many of their old friends continued at primary school until aged 14 and then went to work. Girls were sometimes glad to get back to school to see friends and have the companionship again.

Ladies who attended Celbridge in the 1930s and 1940s are still in contact with friends they made in school.

Homesickness and Runaways

Malory Towers pupils settled in quickly for the most part. Indeed, those who are homesick are almost scoffed at by others. Two girls run away and the ringleader is expelled for numerous reasons. Another girl breaks the rules and goes to the local town for an evening show, she is “punished” by getting lost in a storm on the way back and her health suffers as a result.

In Celbridge, the first year girls were often homesick for some time although others revelled in knowing they had got the scholarship, were attending an academic school and were going to make lots of friends. One pupil sprinkled writing paper with water when sending letters home, to try and get more sympathy from her parents. Another shed real tears over her letters and had the headmistress summon her to her office to ask why she was upsetting her parents by doing such a thing. Some admitted to crying every night for a whole term.

Sometimes girls did run away but it sounds like they were always discovered. One girl tried to run away by getting on the local bus. However, she hadn’t realised that a member of staff always travelled on that bus on her half day and of course, that was the day. The girl was brought back to the school. Even though she was shouting and making a racket outside the classrooms, she wasn’t punished but was sent to bed and given staff meals for the rest of the day much to the envy of the rest of the school.

Another girl attempted to run away but was spotted by a local person who knew she should not have been out at that time. He telephoned the school. A couple of local people with cars (the staff didn’t have cars then) offered to join in the search. Some staff set out on bicycles. One of the staff in a search party car spotted her a little way along the road to Dublin. As the car pulled in and the window rolled down, the girl began to ask for a lift. She got a huge shock when the car stopped and she saw the teachers sitting in it.

Another runaway got onto the farmer’s cart that delivered the milk and was later discovered fast asleep on it. Two girls could not be found one summer term. They had climbed over the boundary wall and onto a hayrick and gone asleep. Eventually they turned up. Jumping over the wall into the neighbouring fields wasn’t always the most effective path to take when running away. A third form girl tried that one day, and had to dash back as an angry bull didn’t like the look of her.[6]

One day a girl disappeared and couldn’t be found anywhere. The school premises were searched though the likelihood of her being there was quite slim. However, it had once happened that a girl had locked herself into a clothes locker. Staff and neighbours started searching further afield but to no avail. She was eventually discovered in the Sports Pavilion, lying close under the window so the possibility of being seen from outside was almost impossible.

Outside Events

The Malory Towers books had little or no reference to what was happening in the outside world, incredible when they were just written after the Second World War. Compare this to the Chalet School books, where pupils were directly caught up in escaping danger during the WW2.

How aware were the Celbridge girls of outside events? The Irish Times newspaper was available each day. In 1947, they borrowed a wireless from a neighbouring family and sat, agog, listening to commentary relaying the wedding of Princess Elizabeth. However, they only heard about the 1948 Triple Crown rugby win when walking to church when one girl overheard someone talking about it. One pupil, Rene Earle, brought back a radio and those in Middle Grade and above were allowed to listen to it in the library on Sunday afternoons. All the girls crowded around it, loving listening to the Top Ten on Radio Luxembourg. Some also remembered getting up to listen to Cassius Clay fights at 3am.

Life after Celbridge

Just as the Malory Towers girls had huge pride in their school, the Collegiate School Celbridge girls were the same. Miss Lynd used to say “Celbridge girls wouldn’t do …” so they all knew there were academic and behavioural standards to be upheld. One pupil remembers her father saying “a Celbridge girl can go anywhere”, it was seen as a passport to a good future.

As it got closer to the end of the academic year, girls looked forward to going home. One night, on the eve of departure at the end of term, the teacher on duty was doing her usual rounds of the dormitories about 11:00pm when she was met by this sight: a second year pupil lying on her bed fully dressed with hat and coat on so that she would be ready to depart at an unearthly hour to the train station. She had a long journey ahead of her as she lived in Kerry and wasn’t going to risk missing the train. Memory does not recall what action was taken by the teacher.

Those leaving the school for good had mixed feelings: looking forward to the next chapter yet realising that it was going to be hard to stay in touch with good friends. Most girls left after the Intermediate Certificate at this time. Claire Lappin didn’t know that her scholarship could have been extended for two more years as she got honours in her Intermediate Certificate. She and Jean Morton went on to “Miss Galvey’s Secretarial College for young ladies and gentlewomen” in Dawson Street, Dublin. Some went into teaching or nursing; some did secretarial training and got office work.

There you have it, my comparison between real boarding school life and the fictional Malory Towers. Of course, many of the interviewees as well as the content in The Celbridgite magazine may have been viewing school life through rose-tinted spectacles but on the whole, the ladies I interviewed remembered good and bad times. Remember many of them came from situations were food and comforts at home weren’t that plentiful either.

I’ll leave you with this poem by my aunt. She died about 20 years ago and it was a nice surprise to find it published in the school magazine. She was my dad’s eldest sister and got a scholarship to Celbridge.

Farewell Thoughts by Millie Sixsmith (1948) published in The Celbridgite 1964-65

Six years I dwelt in Celbridge School,

Trying to keep each single rule,

Working but in fits and starts,

When conscience pricked with fiery darts.

Six years passed quickly, day by day,

Each one in the same old way –

Class and study, study, class –

A routine dreaded by many a lass.

But lectures on Fridays, and lantern slides

Are surely the memories that will abide.

For I know that the troubles will be forgot

As soon as I in this school am not

And I shall remember the pleasant times

Spent in Celbridge ‘neath the limes,

Which border the avenue with living green,

Where birds and squirrels may oft be seen,

Trees that thus for long have been.

Dear faces shall come back at memory’s call

And I hope I shall remember all

Those who, while here, have been dear to me

And whom again I may never see.

Farewell, Celbridge, soon I go –

Where, as yet, I do not know –

Never again to enter your walls

In navy dress, or stand in your halls,

Or ring the gong of sullen sound,

Or walk about the grassy mound –

Far from school I shall have gone

Though it in my memory will linger on,

While I shall be forgot ere long –

The noble trees, the old grey walls,

The ceilings high and the long, long, halls

Will be the same as had not I

Ever within them heaved a sign.

O trace will be my passing have left therein

Beyond a name in roll-books thin –

A name to be read in future years

By those then prone to school-girl fears.

This is of life the common way –

Forgot will be the things we say,

Our deeds will be forgot by men

Once we have passed beyond their ken.

[1] Blyton, Enid, First Term at Malory Towers, (Granada Publishing Limited, 1976 edition) p13-14.

[2] Notes of Freda Yates, 2017

[3] First Term at Malory Towers

[4] Interview with Claire Lappin

[5] Memories by Hester Walsh in The Celbridgite Magazine 1970-71

[6] Whiteside, p200

Alison McMullen

I really enjoyed this, Lorna. I was boarding in the Hall School 1968-1971. Brings back memories!

Nekarsulm

Your blog mirrors a lot of the conditions snd experiences of boarding in The Royal School in the late 1970’s.

Although, we thought our privations resembled Tom Brown’s Schooldays more than anything written by Enid Blyton.

Nekarsulm

Your reminiscences of Celbridge ring true, and are very similar to attending The Royal School, Cavan at the end of the 1970’s.

We thought our experiences were more similar to Tom Brown’s Schooldays than anything penned by Enid Blyton however!

Being in the boys dorm, things were far from genteel, with slipper fights, various wrestling matches (organised by Prefects, and involving 1st Year’s) and other less wholesome activities.

Lorna Post author

Yes, I think the boys school at KCK was a lot rougher than the girls school at CSC. We did have pillow fights and midnights feasts still in the 1980s 🙂

Wild Atlantic Mum

Really enjoyed this Lorna. I’ve long been fascinated by boarding schools as I was also a huge Malory Towers fan (and St Clares – have you read those?). Great to get an insight like this into an Irish boarding school. I suspect that once my homesickness faded I would have quite enjoyed it!!

Lorna Post author

Yes, I also read St Clare’s, and the Naughtiest Girl series, and the Chalet School. Loved them all.

We had midnights feasts in the 1980s but otherwise, it wasn’t much like MT I have to say. I made good friends though and there’s seven of us who still meet u about twice a year. Meeting up more often this year as meeting up for a meal for each of our 50th birthdays, two done so far, the rest are next year.

BUY THE BOOKS NOW

Subscribe to My Blog Posts

Subscribe to My Newsletter

Recent Posts

Archives

Categories