Some fields are named after their draining abilities (e.g The Bog), or their size (e.g. The Long Meadow). Two of our fields, High Shores and Low Shores, are named after a previous owner. My great uncle Herbert Sixsmith bought about 80 acres at Garrendenny, and purchased these two fields sixteen years later (around 1925). They were owned by a farmer, John Shore, who also worked as a carman delivering coal by horse and cart. He lived nearby and he had right of way up along the avenue to the gateway at Low Shores. He rose early and set off with his horses and cart to collect coal from the mines and then deliver it. One day it came to Herbert’s attention that these horses weren’t being grazed on Low or High Shores at night, but were in fact being retrieved early from Herbert’s fields. They were put into Low or High Shores in the afternoon but at some stage during the late evening, the gate was opened and they were being let out to graze Herbert’s grass. Hoof marks were spotted in fields that Herbert knew his own horses hadn’t been in. One night, he and his workman, knowing the carman’s horses had been newly shod, caught both of them, led them to the stable and removed their shoes before releasing them. Funnily enough, the unwelcome grazing stopped. Herbert purchased the two fields soon after that. It is not known what Shore had named them but since then, they have been named after him.

My dad has mixed memories of High Shores. It was the field used for growing beet and while farmers loved this crop, seeing it delivering payment at an otherwise lean time of year (December), their children hated it. It was hard work in inclement conditions, whereas before beet was introduced, the winter months were a time of year for finishing work early and for doing most of the work in dry sheds. Now, however, they were out in the elements.

They grew three acres of sugar beet, which doesn’t sound a lot, yet it kept them busy for weeks. When harvesting in winter, they wore waterproof aprons to protect themselves from the weather. The harvesting was a slow process as the beet had to be pulled by hand. They tugged two beets at a time from the frozen ground, one in each hand, then hit them against each other to knock off the worst of the clay. The beets were put into piles, with the roots in and leaves facing out. If it was going to be frosty, the pile was covered with beet tops, as frozen beet deteriorated quickly and was unfit for the manufacture of sugar.

One year, cattle from the neighbouring field broke into High Shores and ate the beet tops. This meant there were no leaves to tug when trying to remove the beets from the cold, hard ground. The men couldn’t use a pitchfork or spade for fear of damaging the beets, so they had to dig with their fingers to manoeuvre the plants out ‘by the shoulder’. Dad can remember kicking at them – both in frustration and to shift them out of the solid ground.

High Shores is one of our favourite fields. Brian likes it because it is our driest field. When conditions are proving difficult on our heavy soils, the cows can still graze High Shores without doing damage. I love it whatever the weather is doing. When the wind is blowing a gale and the grey sky is merging with the dark hues of the horizon, I can stand up there and feel exhilarated. The wind may be blowing my breath down my mouth and throat, but the fields stretch out beneath me, making me feel like a giant who could put her feet on each patchwork field and march all the way to the horizon. On calm bright days, the horizon is much further away, and the ‘top of the world’ feeling still thrills me. Kate experiences the same exhilaration when walking across that field, which makes me wonder whether it’s a female thing – a case of like mother like daughter? A walk across hilly fields with fine views always results in us coming home in much better moods, relaxed and empowered all at once.

High Shores is now divided into two: the top half is flat and backs onto Garrendenny Lane; the bottom half slopes down, parallel with the wood I used to think was so huge when I was a child seeking adventures and trees to climb. There’s history here too: there were two large hollows where gravel was dug out by hand in the 1930s, for building projects. Perhaps the gravel was used for the hayshed, built in 1932, and still used every year. We filled in one of the hollows this year as it tended to become a pond during wet weather. Nice for wild ducks, but not so good for the grazing cows. We removed the top soil and covered the hole with many loads of earth dug out when making room for a new shed in the farmyard. The top soil was replaced and grass seeds sown. In one way we were removing history; in another way, we were creating it by improving the field.

High Shores is the field that holds more memories for me. We walked to visit neighbours on winter evenings when the snow was four inches deep and the full moon meant there was no need for torches. Like ramblers of the past, we climbed over a gate to get out onto the lane and tramped along the rough ground in boots, muffled up with hats and scarves against the cold. After tea, whisky and chat in the neighbour’s house, it was time to ramble home again. Once it would have been relatively busy for a rural country lane, but unlike times gone by, we didn’t meet anyone on our way home.

There was also the windy day I was riding my pony, Lucy, there. She didn’t want to ride into the wind, but we’d gone a distance with the wind behind her, so she had to turn around. Lucy’s stubbornness matched mine, but she had the advantage of strength. Whether she decided she would join me in the exhilaration of running into the wind or that the handiest way to get rid of me was to bolt, off she suddenly took. She reared up and I ended up on the ground. Dad was fencing nearby and got a shock when he saw Lucy bolting down the hill and no sign of me. He was convinced I was on the other side of her, my foot caught in the stirrup as I was dragged along. I then appeared over the brow of the hill, cross that Lucy had outsmarted me and determined not to let her get away with it. I got back on eventually, but we both knew that she had won the battle as we rode home with the wind behind us.

Low Shores has many springs and has been drained a few times. It has a steep sandy bank leading to a peaty hollow. The first water pump was placed there to pump water to the yard and house. When we reseeded it a few years ago, a tree trunk buried in the peaty hollow emerged. It was perfectly preserved and just might become a mantel in my new library – if the builders ever return to finish it!

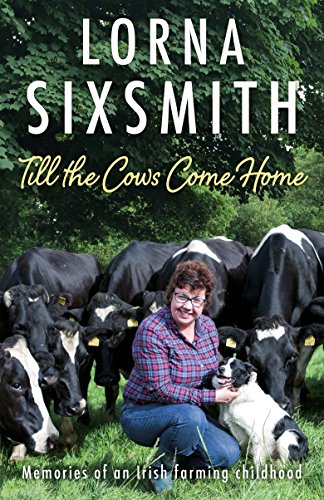

Till the Cows Come Home

There are more stories of our fields in my memoir Till the Cows Come Home which was published in 2018. I’m very grateful to the farmers, authors, bloggers and reviewers who provided reviews. Here’s one from Emma Lander:

There are more stories of our fields in my memoir Till the Cows Come Home which was published in 2018. I’m very grateful to the farmers, authors, bloggers and reviewers who provided reviews. Here’s one from Emma Lander:

“The book documents the history of the family farm and their family and, like any good book, I actually felt Lorna was sat next to me while I read. Such was the warmth of the words and Lorna’s uncanny ability to write like she is talking to an old friend.

The thing is though, Till The Cows Come Home is a history of farming for everyone. All farming families will recognise most of the situations so really, the book is a memoir for everyone.”

If you would like to read Till the Cows Come Home, it is available as an ebook and a beautiful hardback (I am so pleased with its production values, okay, apart from my mug on the front, but the quality of the paper is superb, it includes pages of photographs and even has a cowprint on the interior of the cover). Buy it from Amazon, directly from the publisher Black and White Publishing or bookshops.

Catherine

Friday Fields – great name for a Friday blog ?