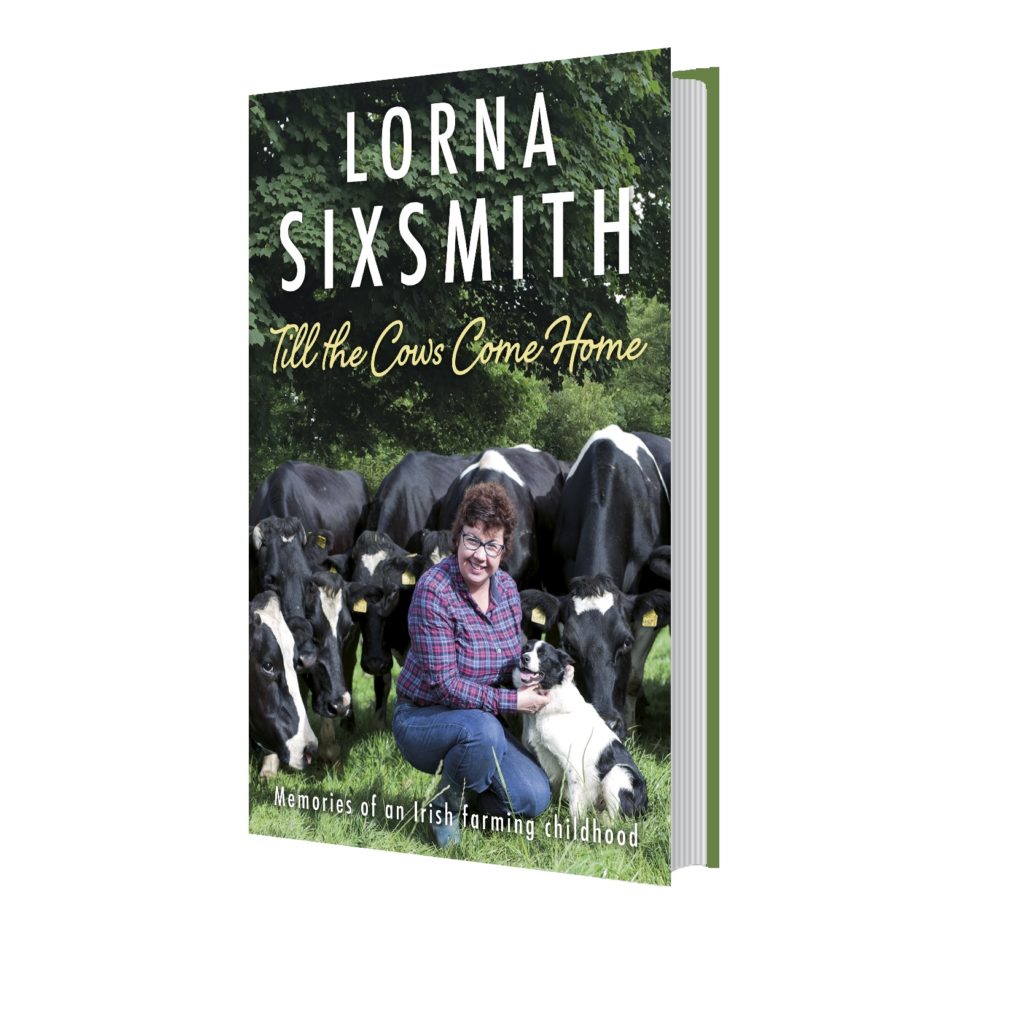

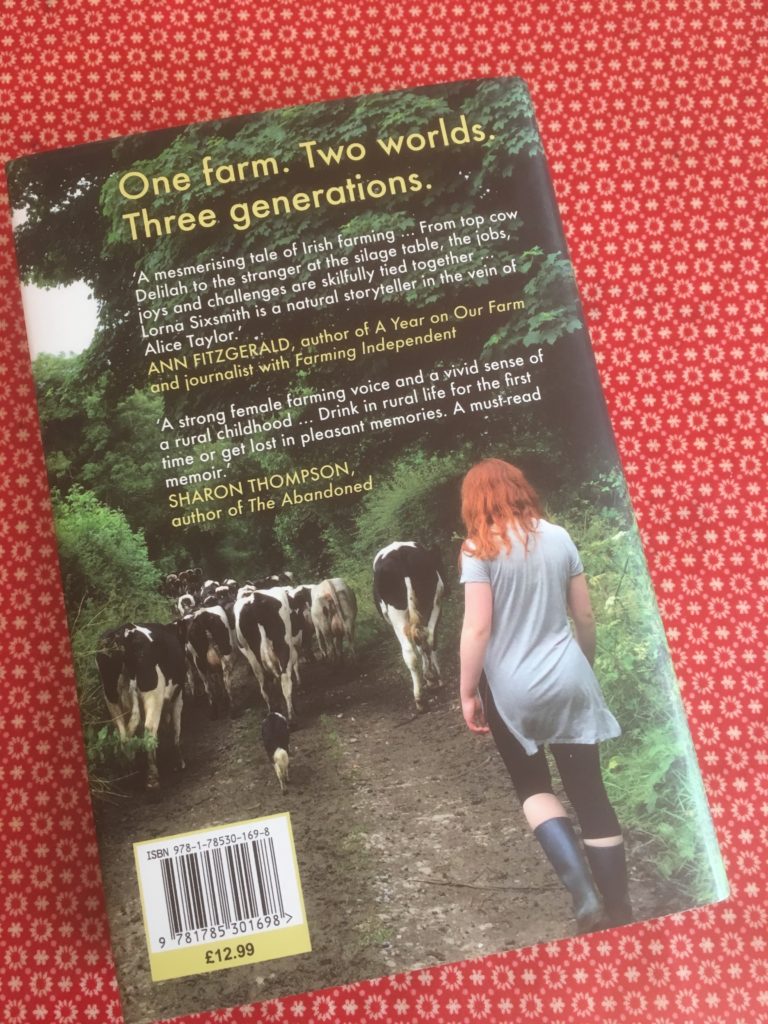

Writing a memoir was a slightly daunting task. I intended to share stories from over three generations of family farming, mainly recounting stories from our childhoods: my dad’s from when they moved to Garrendenny in 1945 when he was 7 years old, my childhood of the 1970s and also to provide stories from when we took over the farm in 2002 showing how why many things have changed, some elements remain very similar for children, no matter what era they are born into.

One of the first conundrums was working out how to structure it. Many memoirs, as you’d expect, are written chronologically. Some may have a story from the present to start and provide flashbacks. Some start at the beginning and then proceed to tell stories through the decades. I decided to have chapters on different subjects areas e.g. Straw, Silage Making, Cures and Superstitions, Christmases, Mechanisation and so on. The chapters containing more stories from the 1920s-1960s went earlier in the book and those containing more modern stories were placed later. The chapter on ‘Straw’ was actually the first to be written as the pitch to the publishers was comprised of a childhood escapade where I was convinced I had used up one of my nine lives during the straw-making season.

The opening chapters also share the history of Garrendenny: those who lived here before us and what happened to them, the tenants who rented the fields and how their names are still used, how the farm came into Sixsmith ownership, what the surrounding countryside was like and the importance of the coal mines to the local economy and so on. But first I wanted to share my feelings on coming back to farm from our city lives in the UK where we were working in permanent pensionable jobs with good holidays and why I had never really envisaged myself as a farmer.

Extract

The opening section was subtitled The Unlikely Farmer – I hope you will read on and enjoy:

Garrendenny Farm has been home to the Sixsmiths for over one hundred years. When I left in 1987 to spread my wings, I never imagined myself back here, let alone farming. Yet, in July 2005, there I was, gasping for breath in the middle of a field trying to catch a runaway calf.

Garrendenny Farm has been home to the Sixsmiths for over one hundred years. When I left in 1987 to spread my wings, I never imagined myself back here, let alone farming. Yet, in July 2005, there I was, gasping for breath in the middle of a field trying to catch a runaway calf.

‘Can you not run faster?’ I heard Brian shout as I tried, in vain, to stop the calf. She raced past me, ignoring my waving arms. She slowed down a hundred yards from us but still watched us carefully. Her head and tail were raised high, signifying she was ready to gallop again. I stopped to draw breath.

It was coming up to our third farming anniversary. We had just moved into the farmhouse and here we were on a Sunday morning, trying to retrieve a four-month-old calf from a neighbour’s field. Eighty calves had been put into Peter’s Field the previous day and, when herding them that morning, Brian noticed one was missing. Somehow, calf number 1342 had squeezed through the hedge and into a neighbour’s field. It was a large field divided into paddocks by electric wire; yearling Charolais cattle viewed us with some curiosity from one of them. The last thing we wanted was the calf getting in with them or running through another hedge into a further field. It would be impossible to retrieve her if that happened so we absolutely had to get her back.

This was the third time we had tried to run her towards a corner, hoping that her brain would register it would be a good idea to squeeze back through the now enlarged gap in the hedge and rejoin her friends. So far it hadn’t worked. It wasn’t easy to round up a single calf – and this one was too flighty, too skittish, too fast. She had probably been stung by the electric wire too and was scared of it happening again.

‘We’ll try again,’ said Brian with the look of a man who was going to die trying. And I could tell Dad was just about to say, ‘It’ll never work,’ when Brian went marching off again in pursuit of the runaway.

For a split second, I allowed myself to remember my pre-farming life. Sunday mornings were usually devoted to decorating or reading the newspapers over a leisurely breakfast. Even sanding architraves would be more relaxing than this. We used to reward our efforts with a pub lunch or a picnic in the New Forest, followed by a leisurely stroll for a couple of hours. I groaned as I started to jog after Brian. I wasn’t fit; it was about four years since my last aerobics class. I wasn’t wearing a sports bra, my jeans were belt-less and kept slipping down and the ground was so rough I was convinced I’d break or sprain an ankle if I didn’t watch my step. I didn’t respond well to shouts from my husband to run faster either. I wasn’t cut out to be a farmer at all.

We created a semicircle around the calf, each of us holding out a stick to elongate our arms and try to create a barrier, and in this way we closed in on her slowly. Thankfully she took the hint and walked in the right direction as we whispered encouragement to her. We got closer this time; at last she was going towards the corner. We had enlarged the gap she had escaped through, and we had to just cross our fingers that she would go back through it. The other calves were at the other side of the hedge now, maybe their presence would encourage her. She walked closer and closer as we closed in tighter and tighter. She seemed to be concentrating on the other calves now rather than being wary of us. She climbed up the small incline and Brian raced forward to push her on further. We’d done it.

Calf number 1342 spent the rest of that summer with her comrades on the outfarm as I started to adjust to rural life, helping out at fundraisers, cooking for contractors and getting to know the neighbours. Two years later, as she had her first calf and entered the milking herd, our eldest child started primary school and I got a position on the school’s board of management. Was I starting to settle into rural farming life after years of being a city girl?

Growing up as a farmer’s daughter, I developed a love for the land yet never saw myself becoming a farmer. In Ireland, as in many other countries, farms traditionally passed down the male line. My brother, Alden, was nine years younger than me. I just assumed he would take on the family farm. My extensive list of allergies – to dust mites, dairy products, grass pollens, straw and many other things – probably further indicated that farming wasn’t the best career choice. And I wanted to emigrate, to experience life outside of Crettyard, of Dublin and of Ireland. I didn’t want to marry a farmer, not because of the hard work and long hours, but because

I’d have to live in the same place for decades. I wanted to spread my wings.

Yet, here I was back in Crettyard, destined to live in the same house for the next quarter of a century. Accustomed to renovating a house every two years and moving on, I sensed I’d be moving the furniture around frequently.

It’s true that the tie to the family farm is usually very strong because it has been passed down from generation to generation. No one wants to be the generation to sell that land. It’s a fact that farms in Ireland don’t come on the market as often as in other countries. Land exchanges hands once every four hundred years in Ireland compared to every seventy years in France. I was aware that the responsibility to be a good farmer and hand the farm on to the next generation in an improved state can be a challenge. Could I relish the challenge of being self-employed, loving farm life and being at one with nature? Would it be a dream career and an ideal lifestyle? I had a love for the land, yet would it become a millstone around my neck? Would I feel too tied down by it? Time would tell.

If you would like to read on by purchasing a copy of Till the Cows Come Home, they are in all good bookshops in Ireland and the UK, on Amazon and Book Depository, and in Tesco’s and SuperValu in Ireland.