Aleen Cust was Britain’s first female vet and Ireland’s too as she worked here for many years. Her mother was a “woman of the bedchamber” to Queen Victoria, her father was godson to Leopold, King of the Belgians and they were connected to many influential people. Aleen was born in Co. Tipperary in 1868 when her father worked as an agent. However, he died when she was ten and the rest of the family moved back to England.

Aleen Cust was Britain’s first female vet and Ireland’s too as she worked here for many years. Her mother was a “woman of the bedchamber” to Queen Victoria, her father was godson to Leopold, King of the Belgians and they were connected to many influential people. Aleen was born in Co. Tipperary in 1868 when her father worked as an agent. However, he died when she was ten and the rest of the family moved back to England.

Connie Ford, the biographer and also a veterinary surgeon, surmises that Aleen’s education was probably much more liberal than most girls received as her mother, in straitened economic circumstances, probably let the tutor teach her with her brothers rather than hiring a governess specifically for her. In 1894, Aleen went to Edinburgh to train as a veterinary surgeon and survived on an inheritance of six shillings and sixpence a week. It seems her family disapproved of her choice of career and more or less disowned her. She had family friends who gave her some support. Despite completing the course, she was not allowed to graduate. Some urged her to take the RCVS to court but Ford suggests it was both the lack of money and fear of damaging her mother’s position at court that dissuaded Aleen from doing so. She didn’t try again to get legal entry into the profession until 1922. She won a gold medal for zoology in her first year but didn’t win any more – whether she didn’t go for them or didn’t win is unknown. One respected practitioner said she was one of the best students he ever had on work experience so she was held in high esteem by some people.

She moved to Co. Roscommon, Ireland in 1900 having obtained a post as assistant veterinary surgeon. Apparently she was good at her job, excellent with horses and was quickly accepted by the various clients. In 1906, following a visit to a conference in Budapest, she was invited to read a paper to the Irish Central Veterinary Association. Ordinarily, these meetings were regularly reported in the Veterinary Record but they ignored this meeting! However, it was reported at length in the Irish Times and in the Veterinary News. Ford says the editor of it specialised in differing from the official Veterinary Record whenever he thought fit. Amusing in one way. She was appointed to the role of Veterinary Inspector for Galway County Council (there was a vote of 14 to 10 in favour). Many saw her appointment as an action “agin the Government”. However, the RCVS couldn’t afford bad publicity or the cost of a lawsuit. The Ballinasloe Western News didn’t approve of Aleen and wrote: “The County Council have made an appointment in the horse and brute kingdom which appears to us at least disgusting, if not absolutely indecent! Of the many callings embraced by women, that of judging and doctoring horses appears to us the most unsuitable and repulsive. We can understand women educating themselves to tend women – but horses! heavens!” She was appointed in 1906.

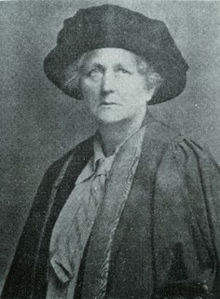

Cust was described by others as a robust, fine-looking, big woman. She travelled to clients on an Arab stallion, or in a gig if she had to carry equipment. Apparently, she changed into a ballgown in the evenings to have dinner. She charged wealthy people £1 or £2 per visit but often gave poor people money when she visited. She supplied the children’s hospital in Dublin with milk from her goats every month or so.

Apparently the priest was scandalised by her castrating of colts and told his parishioners not to employ her but they ignored him. When his cow was ill, villagers were delighted to see her ride up to his house and treat the cow. There were rumours that she and Byrne (her employer) had an affair and she had children but Ford discounts this. She did fall in love with Bertram Widdrington (his parents had been firm family friends when her family moved to England and they gave her a lot of support and encouragement) but they called off the engagement soon after- it seems a mixture between her not wanting to give up their career and realising she wouldn’t be able to settle as an army wife in India.

At the start of the war, she selected and evaluated horses for requisitioning and apparently the best of the horses came from Roscommon. It seems she worked in France during the war in the “Remount Hut” where horses were assessed and treated although it sounds like records of her are deliberately scanty.

It was 1919 before “The Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act was passed. It provided that a person shall not be disqualified by sex or marriage from “assuming or carrying on any civil profession or vocation, or for admission to any incorporated Society”. At the next quarterly RCVS Council, it was announced in a very short speech that women were now entitled to enter the veterinary profession. Apparently an editor added “it need not concern us greatly, for it is not likely that women will offer themselves in sufficient numbers to be of serious moment”. Aleen received her qualification, finally, in 1922. A tribute was included in the Veterinary Record giving details of her career but The Field added a note of caution regarding her as a wholly exceptional and saying “one swallow does not make a summer, nor does one lady with exceptional physical endowments prove that the veterinary profession is one suitable for women”. The second woman to receive a qualification, Edith Knight, in 1926, struggled to find work and this was a similar situation for many female vets in the years to come.

Aleen returned to a very different Roscommon after the war. Beforehand, rich and poor alike had loved and respected her. Now as an English person, she was regarded with suspicion during the War of Independence and the Civil war. Her house was besieged by the Irish Liberation Army and on at least one occasion, she is said to have held them off with a shotgun. She moved to Hampshire in 1924, saying that the New Forest was the place that most resembled Roscommon. At 56, with a weak chest, she didn’t set up a practice and her income was sufficient for her needs. She bred dogs, attended Veterinary meetings and kept a couple of horses. Her father’s family continued to ignore her but several of her mother’s relatives were good friends. She visited other countries visiting veterinary schools and Ford remembers being in her third year in London College when this handsome lady with a beautiful voice met them.

Some of her Aleen’s tips shows just how resourceful vets had to be at times:

A prolapsed uterus or vagina can be retained by ordinary butcher skewers or string zig-zagged if all your West’s clamps are in use or left at home. Every house has these.

Few cows will kick if the tail is held on a level with or rather above the back.

The screwdriver of your car outfit is quite useful to puncture post-pharangeal abscesses.

If you’ve forgotten your milk fever outfit and have no calcium, borrow a bicycle pump, take out the valve, boil it, use it as a teat syphon and pump away.

A wisp of hay or grass tied into a knot of your castrating rope prevents the knot from jamming.

If a horse will not lead into a stable, try a longer rope and march ahead without looking back at him.

If no funnel is available and you want to pour from a large bucket into a small bottle, grip the bucket with your knees, lay the flat of your thumbs along the rim and let your thumbs form a channel for the water.

Amongst her bequests in her Will, she left the RCVS £5,000 to be invested and to be awarded as a scholarship and expressed a wish that “in deciding between candidates for the scholarship who are otherwise in their opinion of equal merit the Council shall as between men and women give preference to women”. She died in Jamaica, while on a three month holiday to improve her health in a warmer climate, at the age of 68. Ten days after suffering a heart attack, and twenty minutes after treating a dog that was bleeding, she collapsed and died immediately. Ford finishes by saying “Despite the shock to her hosts all realised that it was as she would have wished to go – working in her chosen profession and completing a satisfactory case.”

Amongst her bequests in her Will, she left the RCVS £5,000 to be invested and to be awarded as a scholarship and expressed a wish that “in deciding between candidates for the scholarship who are otherwise in their opinion of equal merit the Council shall as between men and women give preference to women”. She died in Jamaica, while on a three month holiday to improve her health in a warmer climate, at the age of 68. Ten days after suffering a heart attack, and twenty minutes after treating a dog that was bleeding, she collapsed and died immediately. Ford finishes by saying “Despite the shock to her hosts all realised that it was as she would have wished to go – working in her chosen profession and completing a satisfactory case.”

This is a short biography, less than 100 pages and I longed to hear more about Aleen’s personality if more letters from her existed. Diary entries would have been fascinating. It’s an interesting and thorough examination of so much social history though: her aristocratic beginnings in Ireland, from the difficulties experienced by women in entering the professions, how her family shunned her for her career choice, how farmers did take to her quite quickly but religion and politics, by rearing their ugly head, meant that she eventually left Ireland. I first heard of Aleen Cust when at the Teagasc Farm 1916 event and I hope there will be more awareness of women’s achievements in the past, present and future. More is written about her in this blog post and The History Project is an interesting resource for hidden histories.

Mind you, it seems scandalous and ridiculous now that women weren’t allowed to graduate until 1922 let alone having difficulty gaining employment but let’s remember that people still discount women in terms of them inheriting or running farms, yes, even in 2016.

Crossroads Vet Clinic

Great review! Really want to read one! There are more and more books about women inventors and pioneers now